I worked as a legal clerk during the Epstein case… What I saw in those unredacted files made me quit law forever.

I never thought I’d be the person to walk away from a six-figure legal career, but some things change you in ways you can’t come back from.

It was 2019, and I was a junior legal clerk at a firm tangentially involved in the Epstein case. My job was mundane—organizing documents, redacting sensitive information, cross-referencing testimonies. I was twenty-six, ambitious, and convinced that justice was a system that worked if you followed the rules.

Then I saw the files.

Not the sanitized versions the public would eventually see. Not the redacted PDFs with black bars covering names and places. I saw everything. The flight logs with names that made my hands shake. The photographs that made me physically ill. The depositions where powerful men’s lawyers argued over the definition of “minor” like it was a technicality in a parking ticket dispute.

Let me take you back to the beginning. To the moment when I thought I was just another ambitious law graduate climbing the ladder.

I graduated from Georgetown Law in 2016. Top fifteen percent of my class. Summer associate positions at two white-shoe firms. Student loan debt that made my parents’ mortgage look reasonable. I was hungry—not just for success, but to make a difference. I actually believed that law was about justice. That’s what they teach you in Constitutional Law, in Ethics courses, in those soaring opening speeches during orientation.

Maria:

The firm I joined, which I’ll call Morrison & Hale for legal reasons, specialized in white-collar defense and complex litigation. It wasn’t my dream job—I’d wanted to be a prosecutor, to put bad guys away—but the salary was too good to turn down. Besides, I told myself, everyone pays their dues. A few years in private practice, then I’d move to the Southern District and do real justice work.

My first two years were exactly what you’d expect. Endless document review. Summarizing depositions at two in the morning. Coffee runs for partners who didn’t know my name. But I was good at it. Detail-oriented. Fast. I could spot inconsistencies in testimony that others missed. I built a reputation as someone reliable.

That’s why they assigned me to the Epstein matter in early 2019.

I remember the senior partner, Gerald Morrison himself, calling me into his corner office. Floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking Manhattan. Art that cost more than my annual salary. He was in his sixties, silver-haired, with the kind of calm authority that comes from forty years of winning.

“We need someone meticulous,” he said. “Someone who understands discretion. This case is… sensitive. There are reputational concerns for several parties. Your job is to review, redact, and organize. Nothing leaves this building. Nothing gets discussed, even with other associates. Understand?”

I nodded. I’d signed enough NDAs to wallpaper my apartment.

“Good. You’ll be working in the secure document room. No phones. No photos. No copies. Everything you see stays there.”

The secure room was in the basement. No windows. Card-key access. A guard posted outside during business hours. Inside: three computer terminals, all disconnected from the internet. A industrial paper shredder. Boxes and boxes and boxes of documents.

The first week was overwhelming. I was drinking from a firehose. Police reports from Palm Beach. FBI interview transcripts. Financial records showing wire transfers to shell companies in the Caribbean. Emails discussing “massages” and “appointments” in language that was clearly code for something darker.

And the flight logs.

Aisha:

God, those flight logs.

The first time I saw a name I recognized—a former president—I thought it was a mistake. A different person with the same name. But no. The dates matched public records of when he was out of the country. The destinations matched. And the names of the girls listed as passengers… some of them were clearly aliases, but others had ages next to them.

Fourteen. Fifteen. Sixteen.

I sat there staring at the screen, my coffee getting cold, trying to process what I was looking at. This wasn’t theoretical. This wasn’t allegations in a tabloid. This was documented travel with underage girls to private islands and foreign countries.

And this was just one name. There were dozens more.

Tech CEOs. Hollywood producers. British royalty. Hedge fund managers. Scientists. Philanthropists. People who appeared on talk shows and gave TED talks and donated wings to hospitals.

I want to be clear about something: I wasn’t naive. I knew rich people got away with things. I knew the system was tilted. But there’s knowing it intellectually and then there’s seeing it documented in black and white. Seeing the same names appear over and over across years of records. Seeing the payments to the girls afterward—sometimes labeled as “tuition” or “housing assistance,” as if that made it better.

My supervisor on the project was a woman named Patricia Chen. Fifteen years at the firm. Partner track. She’d seen it all, or so I thought. We’d have daily meetings where I’d update her on my progress.

“How are you holding up?” she asked me after the second week.

“Fine,” I lied.

Anna:

She looked at me over her reading glasses. “It’s a lot. I know. But remember—we’re not here to judge. We’re here to organize and protect attorney-client privilege where applicable. That’s all.”

“Some of these people aren’t even our clients,” I said.

“No,” she agreed. “But they’re connected to parties involved in parallel litigation. We have obligations to multiple entities. It’s complicated.”

Sofia:

Complicated. That word became a mantra. Everything was complicated. The jurisdictional issues were complicated. The international law questions were complicated. The question of who knew what and when was complicated.

But some things weren’t complicated at all. Like the testimony of a girl—I’ll call her Maria—who described being recruited at age fifteen from her high school in the Bronx. Promised money to give massages to a wealthy man. Driven to a mansion where the “massages” became something else. Threatened when she tried to leave. Paid in cash and told to keep quiet.

Her testimony was twenty-three pages. Single-spaced. It was detailed and specific and completely credible. She named names. Described rooms. Gave dates. And at the end, she described how she eventually escaped, only to be too afraid to report it for three years because she’d been told that the man had connections to police, to prosecutors, to judges. That she’d be the one who got in trouble.

I read that testimony on a Wednesday afternoon. Then I went to the bathroom and threw up.

When I came back, Patricia was waiting for me.

Fatima:

“First time?” she asked gently.

I nodded.

“It gets easier,” she said. “You build up a wall. You have to, or you can’t do the work.”

But I didn’t want to build a wall. I didn’t want it to get easier. Because getting easier meant becoming numb to the suffering of children. It meant treating their trauma as just another item in a filing system.

Still, I kept working. I told myself I was doing something important. That proper organization of evidence could actually help bring people to justice. That the redaction process was about protecting victims, not perpetrators.

Emily:

That was before I understood how the redaction process actually worked.

See, there were different levels of redaction. Level One was straightforward: protecting victim identities. Their names, addresses, identifying details. That made sense. Those girls had been through enough without having their names splashed across the internet.

Level Two was protecting ongoing investigations. If law enforcement was still pursuing leads, you didn’t want to tip off potential defendants. That made sense too.

But Level Three… Level Three was where things got murky.

Level Three was “protecting the interests of non-party individuals.” In practice, that meant redacting the names of anyone powerful enough to have lawyers who could make our lives difficult. It meant removing context that might implicate people who hadn’t been charged. It meant editing testimony to remove identifying details about anyone who wasn’t a direct defendant.

I remember the exact conversation where I started to understand.

There was a deposition transcript—a victim describing a party in New York where she was passed around to multiple men. She named five of them. Three were already public figures in the case. The other two…

“We need to redact these names,” Patricia told me.

“Why?” I asked. “She’s testifying under oath. This is evidence.”

“Because they’re not charged with anything. Because naming them opens us up to defamation claims. Because their lawyers have already reached out to warn us about the consequences of public disclosure.”

“But she’s describing crimes.”

Ling:

“Alleged crimes. And without corroboration, it’s her word against theirs. These men have resources. They will bury us in motions. They will sue the estate, sue the victims, sue anyone involved in releasing unredacted materials. The cost-benefit doesn’t work.”

I stared at her. “So we just… protect them?”

“We protect our clients. We follow the law. We do our jobs.” She softened. “Look, I know how this feels. But you have to understand—going after every name in these files would take a hundred years and a billion dollars. The system isn’t designed for that. We focus on the main perpetrators. Epstein. Maxwell. The people we can actually convict.”

“And everyone else walks free.”

“Everyone else is outside our scope.”

That night, I couldn’t sleep. I lay in my apartment, staring at the ceiling, thinking about all those names I’d seen. Thinking about how many of them would never face consequences. How they’d go on living their lives, attending galas, running companies, shaking hands with world leaders.

And I was helping them.

Priya:

The next day, I started keeping a list. Nothing detailed—that would have violated my NDA. Just a count. How many names I saw that would eventually be redacted. How many victims’ testimonies would be edited down to remove context. How many pieces of corroborating evidence would be deemed “not relevant to the primary case.”

By the end of the month, I had:

- 47 names that appeared in flight logs but would be redacted

- 23 individuals mentioned in victim testimony who would be anonymized as “Individual-1,” “Individual-2,” etc.

- 14 sets of financial records showing payments to victims that would be excluded from public filings

- 8 properties where abuse occurred that would be listed only by city, not specific address

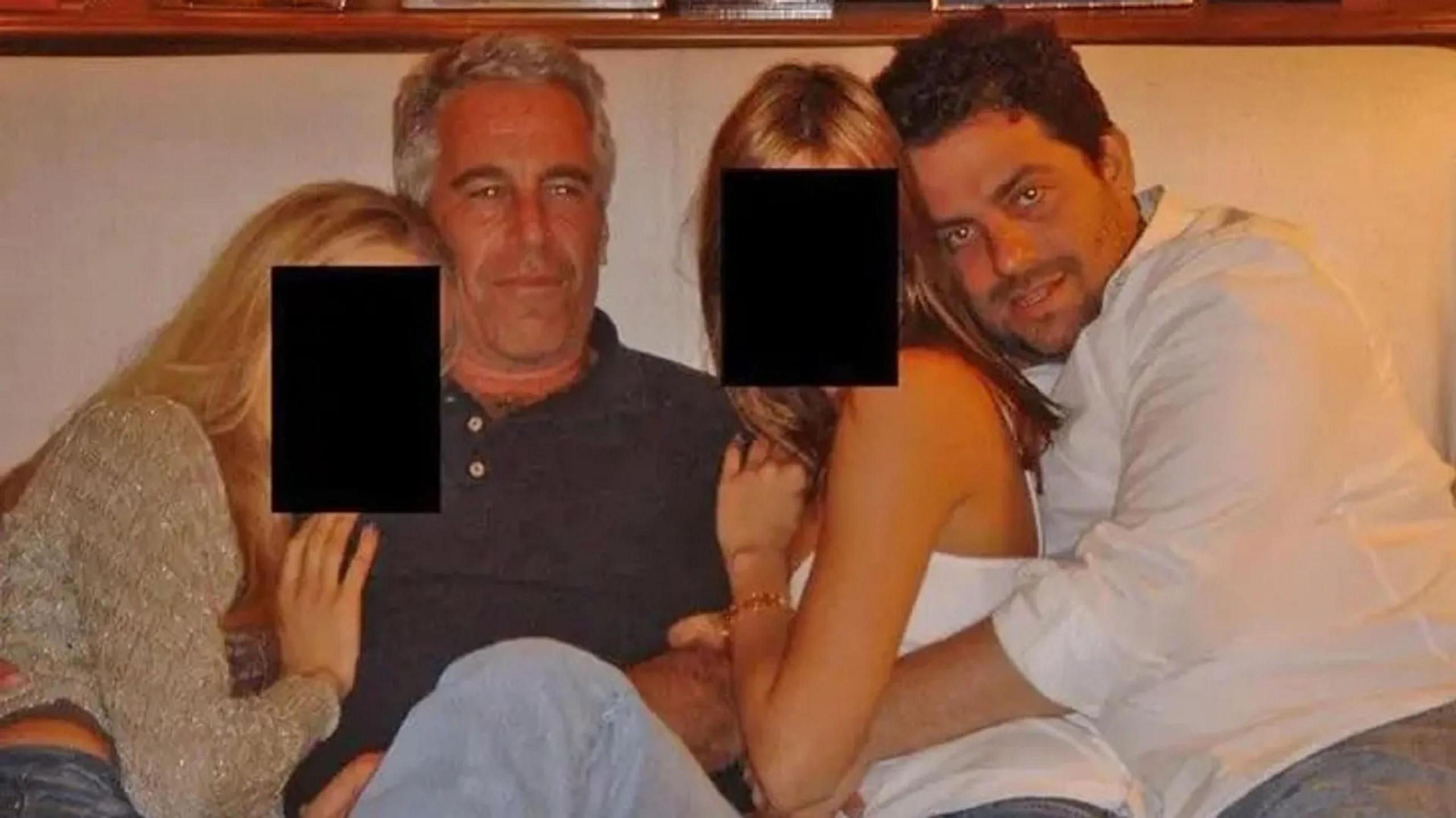

- Countless photographs that would never see daylight

And that was just from the materials I personally handled. There were three other attorneys working on different aspects of the case, seeing different documents.

I started having panic attacks. I’d be on the subway, heading to work, and suddenly I couldn’t breathe. The walls would close in. I’d think about walking into that basement room and spending another eight hours reading about the systematic abuse of children, all while carefully editing out the names of the men who abused them.

My girlfriend, Sarah, noticed. We’d been together since law school. She was working for a nonprofit, doing immigration law. Real justice work. The kind I’d wanted to do.

“You’re different,” she said one night over dinner. “You barely talk anymore. You don’t sleep. You’re angry all the time.”

“I can’t talk about it,” I said. “NDA.”

Olga:

“I’m not asking about your case. I’m asking about you. Are you okay?”

I wasn’t. But I didn’t know how to explain it without explaining what I was seeing every day. How do you tell someone that you’ve lost faith in the entire justice system? That you’ve seen proof that powerful people can literally get away with anything?

“I’m fine,” I lied. “Just stressed.”

She didn’t believe me. But she also didn’t push. That was our relationship—we gave each other space, maybe too much space.

The breaking point came in July 2019.

I was cross-referencing testimonies—trying to find corroboration for various victims’ accounts. If multiple girls independently described the same room, the same procedures, the same people, it strengthened the case.

I found a pattern. Three different girls, recruited from three different states over a span of five years, all described the same man at different locations. They described his voice, his appearance, his specific requests. The details matched. This wasn’t coincidence. This was corroboration.

I brought it to Patricia excitedly. “Look at this. Three independent witnesses. They never met each other. They’re describing the same perpetrator.”

Isabella:

She looked at the files. Then she looked at the name I’d circled.

“No,” she said.

“What do you mean, no? This is evidence. This is exactly what we need—”

“This person is not part of our case. He’s not charged. He’s not a defendant. And he has very, very good lawyers.”

“But—”

“Listen to me carefully.” Her voice was hard now. Not the kind mentor, but the hard-nosed partner. “If we include this, even as a redacted reference, his legal team will know. They will file motions to suppress. They will argue that we’re trying to taint potential jury pools. They will tie this case up for years. And more importantly, they will come after this firm. After you. After me. Do you understand?”

“So we just ignore it.”

“We focus on what we can prove against the defendants we have. We do our jobs.”

“Our jobs are protecting child rapists.”

The words hung in the air between us. I’d said what we’d both been carefully dancing around for months.

Patricia’s face hardened. “Your job is document review and redaction according to the guidelines you were given. If you can’t do that job, maybe you should reconsider your position here.”

I should have backed down. I should have apologized and gone back to my desk and kept my head down. But something in me broke.

“How do you sleep at night?” I asked.

“I sleep fine. Because I understand how the system works. I understand that perfect justice is a myth. I understand that we do what we can within the constraints we have. And I understand that self-righteous associates who can’t handle moral complexity don’t last long in this profession.”

She was right about that last part, at least.

I went back to the secure room. I sat down at my terminal. And I stared at those three testimonies, those three girls who had independently described the same predator, knowing that their voices would be edited into nothing. Redacted into anonymity. Filed away where no one would ever connect the dots.

That’s when I realized: the system wasn’t broken. It was working exactly as designed. It was designed to protect power. To ensure that wealth could buy silence. That connections could purchase immunity.

The law, the thing I’d dedicated years of my life to studying, the thing I’d gone into debt for, the thing I believed in—it was just another tool for the powerful to maintain their position.

I don’t remember making the decision to quit. I just remember walking out of that room, taking the elevator up to Morrison’s office, and telling his assistant I needed to see him.

“I’m resigning,” I told him when I finally got in. “Effective immediately.”

He barely looked up from his computer. “You have a contract. Six months’ notice or you forfeit your accrued bonuses.”

“I don’t care.”

That got his attention. He studied me for a moment. “What happened?”

“I can’t do this anymore.”

“Can’t do what? Your job? Because I have to tell you, walking away from a position like this in your third year—that’s career suicide. You’ll never work in law again.”

“Good,” I said. And I meant it.

He leaned back in his chair. “You saw something that bothered you. Something in the files. And now you think you’re taking a moral stand.”

I didn’t answer.

“Let me tell you something about moral stands,” he continued. “They’re expensive. They’re lonely. And they accomplish nothing. You think if you quit, those files change? You think someone else won’t do your job? You think your noble exit makes one bit of difference to anyone?”

“It makes a difference to me.”

He laughed. Actually laughed. “You’re twenty-six years old. You have no idea what you’re throwing away. In ten years, you’ll be working some dead-end job, drowning in debt, and you’ll realize that your principles were a luxury you couldn’t afford.”

“Maybe,” I said. “But at least I’ll be able to look at myself in the mirror.”

I walked out. Didn’t clean out my desk. Didn’t say goodbye to colleagues. Just walked out of the building and into the July heat and realized I had no idea what came next.

The firm held my last paycheck. They threatened to sue me for breach of contract. They sent lawyers’ letters warning me about the consequences of disclosing confidential information. They made my life hell for about six months.

But they couldn’t make me go back.

Sarah left me three months later. “I can’t watch you destroy yourself,” she said. She wasn’t wrong. I was destroying myself. I was drinking too much. Not sleeping. Burning through my savings. Applying for jobs and getting rejected when background checks showed I’d walked away from a prestigious position with no explanation.

The depression was heavy. Some days I couldn’t get out of bed. I’d lie there thinking about those girls, about their testimonies, about how I’d spent months carefully editing out the parts that mattered. How I’d been complicit in a massive cover-up.

I thought about going to the press. But I’d signed ironclad NDAs. Violating them would mean prison time, not just lawsuits. And besides, what would I even say? I didn’t have copies of documents. I didn’t have proof. Just memories and trauma and rage.

Then Epstein died.

August 10, 2019. Found dead in his cell. Official ruling: suicide.

I was in a bar when the news broke. CNN on the television above the bartender. “Jeffrey Epstein found dead in Manhattan jail.”

The place erupted in speculation. Conspiracy theories flying. People taking out their phones, posting on social media. Everyone had an opinion.

I just sat there and laughed. A bitter, broken laugh that made the guy next to me edge away. Because of course he was dead. Of course. Why wouldn’t he be? Dead men can’t testify. Can’t name names. Can’t make deals with prosecutors that might implicate other people.

Convenient. That’s what it was. Convenient.

Whether someone killed him or he killed himself or it was sheer incompetence… it didn’t matter. The result was the same. The one person who knew everything, who could corroborate every victim’s testimony, who could connect all the dots between all the powerful people… gone.

And with him went any hope of real accountability.

I went home that night and I cried. Actually sobbed. For those girls who would never get justice. For a system that was so obviously rigged. For my own naivety in thinking any of it mattered.

The next morning, I called a nonprofit that worked with trafficking survivors. “I’m a lawyer,” I told them. “Or I was. I want to help.”

The woman on the phone was kind but skeptical. “We mostly need volunteers for direct services. Counseling, housing assistance, that kind of thing. We have legal help.”

“I’ll do anything,” I said. “I just need to do something that actually helps people.”

She heard something in my voice. “Are you okay?”

“No,” I said honestly. “But maybe I will be if I can do something that matters.”

They brought me on as a volunteer. Then, when they saw I was serious, as a part-time staffer. The pay was a fraction of what I’d made at Morrison & Hale. I had to move to a smaller apartment. Had to sell my car. Had to accept that the life I’d planned—the partnership track, the brownstone, the comfortable future—was gone.

But the work mattered.

I sat with survivors. I listened to their stories. Stories like the ones I’d read in those files, but now I was looking at real people, not just testimonies on a page. Women who’d been trafficked as teenagers. Women who’d been failed by every system that was supposed to protect them. Women who were trying to rebuild lives from nothing.

And slowly, very slowly, I started to heal.

Not all the way. I still have nightmares. I still tense up when I see certain names in the news. I still think about those files, about all the names that were redacted, about all the powerful men who faced no consequences.

When the DOJ released portions of the Epstein files in 2024, I watched the news coverage with a mix of vindication and despair. People were shocked. Outraged. Demanding answers.

But I’d seen this before. The outrage cycle. It would last a week, maybe two. Then another scandal would break. Another crisis would dominate the headlines. And people would move on.

Sure enough, within a month, it was old news. The names that were revealed got some bad press. Some PR firms went into overdrive. Some people issued carefully worded denials. But no new charges. No real consequences.

Because the files that were released were redacted. Just like I knew they would be. Black bars over the names that mattered. Context removed. Connections obscured.

The work I’d done in that basement room—that careful, meticulous editing—it had served its purpose. It had protected the powerful while giving the appearance of transparency.

People ask me sometimes if I regret leaving law. The honest answer is: it’s complicated.

I regret that I couldn’t do more. I regret that I saw what I saw and was powerless to expose it. I regret that my silence, even legally mandated silence, meant that predators walked free.

But I don’t regret leaving. Because staying would have killed something essential in me. It would have turned me into Patricia, into Morrison, into all those people who’ve learned to rationalize the unforgivable in the name of pragmatism.

I work with survivors now. It’s hard work. There are no big wins, no dramatic courtroom moments. It’s helping a woman fill out housing applications. It’s sitting with someone while they cry about trauma they experienced twenty years ago. It’s fighting with bureaucracies to get people the benefits they’re entitled to.

It’s small. It’s underfunded. It’s exhausting.

But it’s real. It helps real people. And at the end of the day, I don’t have to lie to myself about what I’m doing or who I’m protecting.

I think about those files every day. About what’s still hidden. About the full truth that the public will never see. About the men who paid money to abuse children and faced no consequences because they had better lawyers, better connections, better luck.

And I think about the girls. The ones who were brave enough to testify, to relive their trauma in depositions and interviews, only to watch their abusers walk away. The ones who see their attackers on television, in magazines, at public events, being celebrated and honored and given platforms.

They deserved better. They deserved a system that believed them, that fought for them, that prioritized their justice over protecting powerful people’s reputations.

They didn’t get it.

None of us did.

That’s the real story of the Epstein files. Not the conspiracy theories. Not the speculation about who killed him or why. The real story is simpler and more devastating: we have a justice system that has tiers. And if you’re wealthy enough, connected enough, powerful enough… you exist above it.

The files proved it. Thousands of pages documenting abuse, naming names, showing patterns. And even with all that evidence, most of the perpetrators faced nothing. Because evidence doesn’t matter when you can afford to make it disappear. When you can hire lawyers to redact. When you have connections that can make prosecutors hesitate.

I carry the weight of what I saw. The names I remember. The testimonies I read. The photographs I had to catalog. It’s a burden I’ll have for the rest of my life.

But at least I’m not carrying it while pretending it doesn’t exist. At least I’m not editing it into palatability. At least I’m not complicit anymore.

That’s not redemption. I’m not sure redemption is possible when you’ve been part of a machine that protected monsters. But it’s something. It’s a choice to step away. To refuse to participate. To do work that actually helps instead of work that enables.

The truth is still out there, buried under redactions. The full story of who did what and who knew and who covered it up. Maybe someday it’ll all come out. Maybe there will be a reckoning.

But I’m not holding my breath.

In the meantime, I do what I can. I help the survivors I can reach. I try to be someone who believes them, who fights for them, who sees them as people instead of case numbers.

It’s not enough. It will never be enough to balance out what I was part of.

But it’s all I have.